Startup Engineering Class: class.coursera.org/startup-001

Balaji S. Srinivasan Signup: coursera.org/course/startup

Stanford University Forums: bit.ly/startup-eng-forum

We begin with an interesting comment on Quora, which we’ve slightly modified:

An idea is not a mockup

A mockup is not a prototype A prototype is not a program A program is not a product A product is not a business And a business is not profits

This doubles as a kind of state machine for your ideas as you push them through to production; at each stage many ideas fail to make it to the next one, both because of time requirements and because of some heretofore nonobvious flaw (Table 1). In particular, while you should be able to get to the program stage with purely technical training, the last three stages are in many ways the most challenging for pure scientists and engineers, because they generally aren’t well taught in school. Let’s see if we can explain why.

Table 1: The idea state machine. Any successful entrepreneur has not one good idea, but a profusion of good ideas that lie abandoned at the beginning of the state machine, at the base of this pyramid. Moreover, many more napkin ideas (e.g. micropayments) have fatal flaws that only become apparent in the implementation stage. It is only through actually pushing ideas through the state machine that one realizes whether they are good or not. It’s useful to actually keep a single Google Spreadsheet or orgmode document with all your ideas, organized by stage in this manner. Expect most to stay at the idea stage!

Stage | What’s required to complete? | Minimum Time |

Idea | Napkin drawing of billion dollar concept | 1 minute |

Mockup | Wireframe with all user screens | 1 day+ |

Prototype | Ugly hack that works for single major use case | 1 weekend+ |

Program | Clean code that works for all use cases, with tests | 2-4 weeks+ |

Product | Design, copywriting, pricing, physical components | 3-6 months+ |

Business | Incorporation, regulatory filings, payroll, . . . | 6-12 months+ |

Profits | Sell product for more than it costs you to make it | 1 year-∞ |

Idea

When it comes to starting a business, the conventional wisdom is that the idea is everything. This is why US politicians and patent lawyers recently pushed for the America Invents Act,

why many people think they could have invented Facebook1, and why reputed patent troll Intellectual Ventures is able to make money from 2000 shell companies without ever shipping a product. In other words, the conventional wisdom is that with the right idea, it’s just a matter of details to bring it to market and make a billion bucks. This is how the general public thinks technological innovation happens.

Execution

An alternate view comes from Bob Metcalfe, the inventor of Ethernet and founder of 3Com:

Metcalfe says his proudest accomplishment at the company was as head of sales and marketing. He claims credit for bringing revenue from zero to more than $1 million a month by 1984. And he’s careful to point out that it was this aptitude

- not his skill as an inventor - that earned him his fortune.

“Flocks of MIT engineers come over here,” Metcalfe tells me, leading me up the back staircase at Beacon Street. “I love them, so I invite them. They look at this and say, ‘Wow! What a great house! I want to invent something like Ethernet.”’ The walls of the narrow stairway are lined with photos and framed documents, like the first stock certificate issued at 3Com, four Ethernet patents, a photo of Metcalfe and Boggs, and articles Metcalfe has written for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal.

“I have to sit ‘em down for an hour and say, ‘No, I don’t have this house because I invented Ethernet. I have this house because I went to Cleveland and Schenectady and places like that. I sold Ethernet for a decade. That’s why I have this house. It had nothing to do with that brainstorm in 1973.”’

In some ways this has become the new conventional wisdom: it’s not the idea, it’s the ex- ecution. You’ll see variants of this phrase repeated constantly on Hacker News. The rationale here is that it’s easy to come up with a trivial idea like “let’s build a social network”, but quite nontrivial to work out the many technical details associated with bringing that idea to market, from large-scale decisions like using a symmetric or asymmetric social network by default to small-scale details like how a “Poke” works. It’s also extremely nontrivial to actually turn a popular technology into a profitable business; just ask Second Life or Digg.

And that’s the reason this phrase is repeated constantly on Hacker News: “It’s not the idea, it’s the execution” is an excellent reminder, sort of a mantra, a whip for them to self- flagellate themselves into a state of focus. It’s also useful for startup novices or dreamers to hear it at least once, as novices tend to assign far too much importance to patents or to seemingly brilliant ideas without working prototypes. As a rule of thumb, early on in a company a patent is only useful as a sort of formal chit to show an investor that you have some kind of defensible technology, and then too a provisional patent is fine. And as another rule of thumb, if someone can steal your idea by simply hearing about it, you probably don’t have something yet that is truly defensible. Compare I have an idea for a social network for pet owners to I’ve developed a low-cost way to launch objects into space.

The net of it is that you can usually be reasonably open about discussing your ideas with people who can give a good bounce, who can understand the idea rapidly and throw

![]()

1Facebook’s backend is highly nontrivial (1, 2, 3) and comparable only to Google. Even with regards to the UI, just as it is far easier to verify a solution than to arrive at one, it is much easier to copy a UI than to invent it in the first place (especially given the knowledge that a billion people found it congenial).

it back with modifications. The vast majority of people are busy with their own things, or aren’t uncreative sorts who are both extremely good at execution and just waiting around to steal your idea. The one exception is Hacker News, and perhaps the startup community more generally. If you have a pure internet startup idea, you should think carefully about whether you want to promote it there before you’ve advanced it to at least a prototype stage. Unless your customers are developers, you need to raise funding imminently, or you want to recruit developers, you don’t necessarily need to seek validation from the startup press and community.

That’s one of the reasons that the execution is prized over the idea: people will copy the idea as soon as the market is proved out. No matter how novel, once your idea starts making money the clones will come out of the woodwork. The reason is that it’s always easier to check a solution than to find a solution in the first place. And a product selling like hotcakes is the ultimate demonstration that you have found a solution to a market need. Now that you’ve done the hard work, everyone is going to copy that solution while trying to put their own unique spin on it. So you’re going to need excellent execution to survive, because sometimes these “clones” far surpass the originals. . . as exemplified by Google’s victory over AltaVista (and every other search engine) and Facebook’s victory over Myspace and Friendster (and every other social network). This is why it sometimes makes sense to keep your head down and grow once you’ve hit product-market fit without alerting competitors to the scale of your market opportunity.

Market

Personally, I’ll take the third position – I’ll assert that market is the most impor- tant factor in a startup’s success or failure.

Why?

In a great market – a market with lots of real potential customers – the market pulls product out of the startup. The market needs to be fulfilled and the market will be fulfilled, by the first viable product that comes along. The product doesn’t need to be great; it just has to basically work. And, the market doesn’t care how good the team is, as long as the team can produce that viable product.

So which is most important: product/idea, execution/team, or market?

One answer is that for a startup veteran or someone who understands any machine learning, the debate is somewhat moot. All these factors (idea, execution, market, team, product) are important to varying degrees; the main point of saying “it’s the execution, not the idea” is to disabuse a novice of the idea that patents matter much at inception, or that a brilliant idea on a napkin2 has much value. You can think of these things on a continuum. Ideas range

![]()

2One argument is that a novel equation or figure is an exception, such as Ramanujan’s notebooks or the Feynman diagrams. Something like that truly is valuable, more in the sense of I’ve developed a low-cost way

in quality from “a social network for dogs” to “Maxwell’s equations”, and execution ranges in quality from “I’ll start a company some day” to “sold or IPO’d company”. As important as the execution is, without a clear vision of where you want your company to go you will never come up with an idea that others want to copy. So how do you come up with a good idea?

The Idea Maze

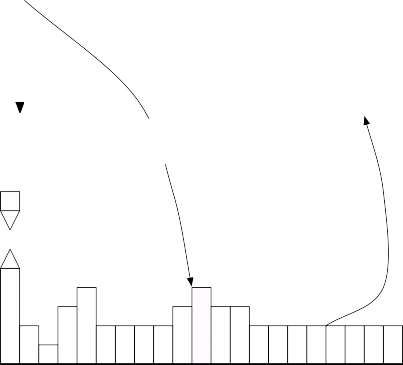

One answer is that a good founder doesn’t just have an idea, s/he has a bird’s eye view of the idea maze. Most of the time, end-users only see the solid path through the maze taken by one company. They don’t see the paths not taken by that company, and certainly don’t think much about all the dead companies that fell into various pits before reaching the customer.

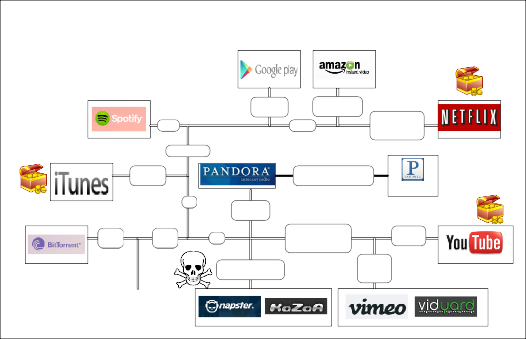

The maze is a reasonably good analogy (Figure 1. Sometimes there are pits you just can’t cross. Sometimes you can get past a particular minotaur/enter a new market, but only after you’ve gained treasure in another area of the maze (Google going after email after it made money in search). Sometimes the maze itself shifts over time, and new doors open as technologies arrive (Pandora on the iPhone). Sometimes there are pits that are uncrossable for you, but are crossable by another (Webvan failed, but Amazon, Walmart, and Safeway have the distribution muscle to succeed). And sometimes there are pitfalls that are only apparent when one company has reached scale, problems which require entering the maze at the very beginning with a new weapon (e.g. Google’s Pagerank was inspired in part by Alta Vista’s problems at scale, problems that were not apparent in 1991).

A good founder is thus capable of anticipating which turns lead to treasure and which lead to certain death. A bad founder is just running to the entrance of (say) the “movies/music/filesharing/P2P” maze or the “photosharing” maze without any sense for the history of the industry, the players in the maze, the casualties of the past, and the technologies that are likely to move walls and change assumptions (Figure 1).

In other words: a good idea means a bird’s eye view of the idea maze, understanding all the permutations of the idea and the branching of the decision tree, gaming things out to the end of each scenario. Anyone can point out the entrance to the maze, but few can think through all the branches. If you can verbally and then graphically diagram a complex decision tree with many alternatives, explaining why your particular plan to navigate the maze is superior to the ten past companies that fell into pits and twenty current competitors lost in the maze, you’ll have gone a long way towards proving that you actually have a good idea that others did not and do not have. This is where the historical perspective and market research is key; a strong new plan for navigating the idea maze usually requires an obsession with the market, a unique insight from deep thought that others did not see, a hidden door. You can often distinguish these good ideas because they require the explanation of an arcane acronym or regulation like KYC (Paypal) or LDT (Genomic Health) or OTARD (Aereo).

The Execution Mindset

We’ve spoken about what good ideas are. What does good execution involve, in concrete terms? Briefly speaking, the execution mindset means doing the next thing on the todo list at all times and rewriting the list every day and week in response to progress. This is easy to say, extremely hard to do. It means saying no to other people, saying no to distractions, saying no to fun, and exerting all your waking hours on the task at hand. The execution

to launch objects into space than I have an idea for a social network for pet owners.

Spotify

Google Play

Amazon Streaming

Netflix

Youtube

Bittorrent

iTunes

Pandora

I've got an idea for doing music/movies on the internet!

no substantial non- monetize

infringing use via paid

accounts

monetize via ads

substantial non-infringing use

(post- Napster)

free

closed source

open source

label deals only

pay

post-iPhone

mobile computer

in every pocket (2008+)

per download

subscription

original non-Hollywood

content

movies

music

Hollywood content

music and movies

The Idea Maze

A "good idea" is a detailed path through the maze. Why does your path lead to treasure: competitor oversight, new technology , or something else?

Figure 1: Visualizing the idea maze. A good idea is not just the one sentence which gains you entrance to the maze. It’s the collection of smaller tweaks that defines a path through the maze, along with explanations of why this particular combination will work while others nearby have failed. Note that this requires an extremely detailed understanding of your current and potential competitors; if you believe you don’t have any competitors, think again until you’ve found the most obvious adjacent market. This exercise is of crucial importance; as Larry Ellison said, “Choose your competitors carefully, as you will become a lot like them.”

mindset is thus about running the maze rapidly. Think of each task on the list as akin to exploring a turn of the maze. The most important tasks are those that get you to the maze exit, or at least a treasure chest with some powerups.

In terms of execution heuristics, perhaps the best is Thiel’s one thing, which means that everyone in the company should at all times know what their one thing is, and others should know that as well. Marc Andreessen’s anti-todo list is also worthy of mention: periodically writing down what you just did and then crossing it off. Even if you get off track, this gives you a sense of what you are working on and your progress to date.

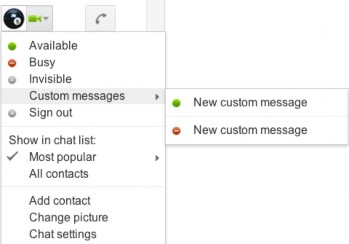

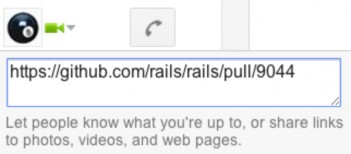

Implementing “Thiel’s One Thing” with Gmail chat status. Good tools can help with execu- tion. For personal tasks, emacs orgmode is highly recommended as it’s completely keyboard driven, works offline, scales from a simple todo list to a full blown document, and integrates arbitrary code snippets. For company-wide tasks, a combination of Github Issues and Gmail Chat status messages can be used to broadcast the link of the issue you’re currently working on.

If there’s something that’s worth nagging people about, it’s keeping their Gchat status up to date with their latest Github issue in this fashion. It constantly refocuses you on your one thing, and allows the entire company to know what that is without constant interrupts. Periodically, you too can scan what others are working on without disrupting their flow.

Figure 2: To implement the “one thing” heuristic with Gmail status and Github issues, set up a new custom message.

Figure 3: Now anyone can click to see the one thing you are working on, and can comment in your ticket. The only thing you are doing is what is in your status.

Startups vs. Small Businesses

It’s useful at the very outset to distinguish between startups and small businesses (see also here). A startup is about growth: it is a play for world domination, an attempt to build a business with global reach and billions in annual revenue. Examples include Google, Facebook, Square, AirBnB, and so on. Startups usually involve new technology and unproven business models. A small business, by contrast, does not have ambitions of world domination. It is usually geared towards a particular geographical area or limited market where it has some degree of monopoly through virtue of sheer physical presence. Examples include pizza parlors, laundromats, or a neighborhood cafe.

With these definitions you can start to see why startups are associated with the internet and small businesses with physical storefronts. It’s easier to scale something virtual from 1 to 1 billion users. Having said that, there are virtual operations that make a virtue out of being “lifestyle businesses” (e.g. 37Signals) and physical operations that yield to none in their ambition for scale and world domination (e.g. Starbucks, McDonalds).

Another important distinction is that small businesses must usually generate profits right away, while startups often go deep into the red for quite a while before then sharply turning into the black (in a good scenario) or going bankrupt (in a bad one3). Ideally one accumulates the capital to start either a small business or a startup through after-tax savings coupled with a willingness to endure extremely low or zero personal income during the early non-revenue- generating period of the small business/startup.

But soon after inception one encounters a crossroads: should you take outside capital from VCs to try to grow the business more rapidly and shoot for the moon, or should you rely on steady organic growth? Taking venture capital is much like strapping a jetpack to a man who’s been running at a nice trot. It could lead to a terrible wipeout or a flight to the moon. The most important consideration in this decision is your own ambition and personal utility function: can you tolerate the failure of your business? Because if you can’t go to zero, you shouldn’t try to go to infinity (1, 2, 3).

Startups Must Exhibit Economies of Scale

So let’s say that you do want to go to the moon rather than build a lifestyle business. Your next step is to do a simple calculation to determine whether a given business is capable of getting there, namely whether it exhibits an economy of scale.

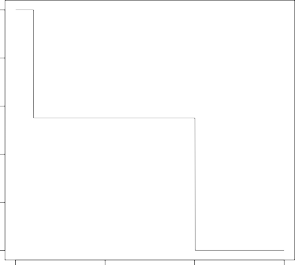

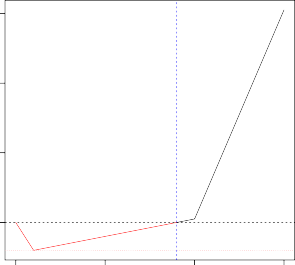

Suppose that we have a startup with the following property: it sells each unit for $1000, but the per-unit cost drops as more units are sold, exhibiting an economy of scale, as shown in Table 2. A table of this kind can arise from an upfront cost of $50,000 for software development to handle the first 100 orders [($1200-$700) * 100], and then another $247,500 [($975-$700)*900] in fixed costs for design/manufacturing revisions to support more than 1000 customers. After those two fixed expenditures, the startup is only paying per-unit costs, like the amortized cost of customer service and the cost of materials.

This simple calculation illustrates many things about the startup world. First, one can see immediately how important it is to shift per-unit costs into fixed costs (e.g. via software),

![]()

3Note though that even a money-losing company is an asset, though: under the US tax code, losses in previous years can be counted against profits in current years, so acquiring a money-losing business for a song can be an excellent way for a large company to shield some profits from taxes (see deferred tax assets).

and why seemingly costly up-front software development can pay off in the long run. Second, one can determine how much capital is needed before the business breaks even; this is one of several calculations that a venture capitalist will want to see before investing nontrivial money into the business. (Note that your low point is usually much lower than in your perfect model!) Third, one realizes how important pricing is; insofar as you are not constrained by competition, you really do want to charge the highest possible price at the beginning in order to get into the black as soon as possible. A seemingly insignificant change from $1000 up to $1200 would completely change the economics of this business and make it unecessary to take on outside capital. Moreover, free or heavily discounted customers generally don’t value the product and are counterintuitively the most troublesome; paying customers are surprisingly more tolerant of bugs as they feel like they’re invested in the item. Fourth, one starts to understand why it is so incredibly difficult to achieve $199 or $99 price points without massive scale. A real product has dozens if not hundreds of cost components, each of which has their own economy-of-scale function, and each of which needs to be individually driven to the floor (via robotics, supply chain optimizations, negotiation, etc.) in order to decrease the overall price of the product. It’s hard to make a profit!

Table 2: A product that exhibits an economy of scale. The cost function is plotted in Figure 4.

Number of units | Cost of production per unit | Revenue per unit |

0 ≤ n ≤ 100 101 ≤ n ≤ 1000 1001 ≤ n | $1200 $975 $700 | $1000 $1000 $1000 |

Cost−per−unit

1000

1100

1200

A product with an economy of scale: costs decline as volume increases.

700

800

900

0 500 1000 1500

Units sold

Figure 4: A product with an economy of scale: costs decline with volume.

Break even point: 900 sold

Minimum initial

capital needed: $20000

Cumulative Profit/Loss

100000

150000

A product with an economy of scale: go into the red, then pull up.

0

50000

0 500 1000 1500

Num. Units sold

Figure 5: A product with an economy of scale: initially one goes into the red, then pulls up.

Startups Must Pursue Large Markets

Even if you can build a product with an economy of scale, you need to ensure that it serves a large market. The annual market size is the total number of people who will buy the product per year multiplied by the price point. To get to a billion dollars in annual revenue ($1B), you need either a high price point or a large number of customers. Here are a few different ways to achieve that magic $1B figure in different industries:

Sell product at $1 to 1 billion: Coca Cola (cans of soda)

$10 to 100 million: Johnson and Johnson (household products)

$100 to 10 million: Blizzard (World of Warcraft)

$1,000 to 1 million: Lenovo (laptops)

$10,000 to 100,000 : Toyota (cars)

$100,000 to 10,000 : Oracle (enterprise software)

$1,000,000 to 1,000 : Countrywide (high-end mortgages)

Now, some of these markets are actually much larger than $1B. There are many more than 100,000 customers for $10,000 cars in the world, for example; the number is more like 100,000,000 annual customers for $10,000 cars. So the annual automobile market for new cars is actually in the ballpark of $1T, not $1B. And that’s why Google is going after self- driving cars: it’s one of the few things that is a substantially bigger market than even search advertising.

Note in particular that low price points require incredible levels of automation and indus- trial efficiency to make reasonable profits. You can’t tolerate many returns or lawsuits for each $1 can of Coke. Relatedly, high price points subsidize sales; it is not 100,000 as much sales time to sell a house as it is to sell a can of Coke, but it is 100,000 as much revenue.

Do Market Sizing Calculations Early and Often

With this basic grounding in market size, take a look at Figure 6. This simple schematic is what many doctorates wish they’d been shown on the first day of graduate school. As background, your modal PhD student works on a project which is technically challenging and highly prestigious within their advisor’s subculture. After six years, if they are entrepreneuri- ally inclined, they might think about commercializing their technology. It is at this point that all too many do their very first back-of-the-envelope calculation on a napkin about the possible market size of their work. And often that calculation does not go well.

Instead, an incredible amount of time and energy could have been saved if at the begin- ning the student had simply enumerated every project s/he found equivalently scientifically interesting, and then rank-ordered said projects by their market size. With all else held equal, if you have committed to spending several years of your life on a PhD, you want to pick the project with the largest market potential.

Among other things, market size determines how much money you can raise, which in turn determines how many employees you can support. As a back of the envelope, suppose that the average Bay Area startup employee costs $100,000 “all in”, with this figure including not just salary but health insurance, parking spaces, computer equipment, and the like. Suppose further that you think you need just five employees for three years to come up with the cure for a rare disease. Then to support just five employees per year is $500,000 per year, not including any other business expenses. But if your market size is only $50M, then you have a problem, because it is going to be very difficult to find someone who will invest $1.5M for three years of R&D to pursue such a small market. Among other things, you won’t capture the entire market, but only a portion. And if it’s going to take three years, that $1.5M could go towards something that has a chance at a $1B+ market.

The best market size estimates are both surprising and convincing. To be surprising is the art of the presentation. But to be convincing, you want to estimate your market size in at least two different ways. First, use Fermi estimates to determine the number of people who will buy your product (top-down market sizing). This will require knowledge of general stats like 300M Americans, 6B world population, 6M US businesses, as well as domain-specific stats like 4M pregnancies (see also Figures 7 and 8). Second, use SEC filings of comparable companies in the industry to get empirical revenue figures and sum these up (bottom-up market sizing); we did this in HW2 with market-research.js. The latter is generally more reliable, though you must be sure that you are not drawing your boundaries too broadly or optimistically (“if we only get 1% of China. . . ”). One of the most convincing things you can do with a bottoms-up estimate is to directly link or screenshot an invoice with a high price point; for example, one has no idea how high the price points in the recruiting or PR markets are until you actually encounter them.

Scientific Novelty (e.g. # of citations)

C. elegans genome

sequencing

2004

Todo lists

Academia

Most Startups

2007

Human genome sequencing

Market size (in USD)

Ideal

Old Economy

2013

McDonald's

If you are choosing between two projects of equal scientific interest, pick the one with the larger market size. And do that calculation up front, not at the end of your six year PhD program.

Figure 6: Qualitative graph of market size (in $) vs. scientific novelty (in citations or impact factor).

So we now understand that a good idea means a bird’s eye view of the idea maze and that the execution mindset means rapidly navigating the idea maze. We also see how market size drives not just the relevance of the company, but also controls downstream parameters like the quantity of money that can be raised and hence the number of employees.

Tools for market research

Let’s now get down to brass tacks and talk about tools for market research. Suppose that you’ve identified a possible market and want to drill down. For example, suppose your hy- pothesis based on recent news stories is that the US dollar will eventually be replaced by the Chinese yuan as the world’s reserve currency, and you believe a service that would make it easier for people to move their bank accounts from USD to RMB would be of value. How would you validate this hypothesis?

First, you’d want to have some news coverage or research papers to establish the overall frame; these will be display pieces in any pitch to investors. Going to Google Books for the history and reading SEC filings and Wikipedia can be extremely helpful.

Next, you want to do a back of the envelope estimate of market size, Googling as necessary for any statistics.

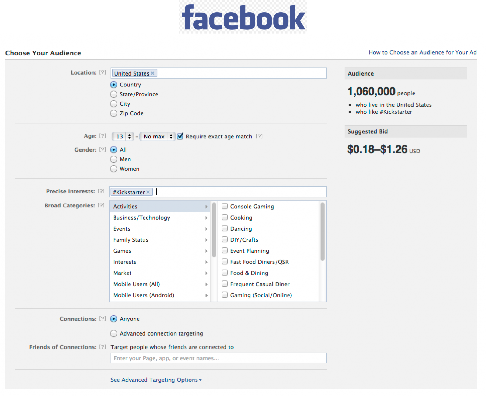

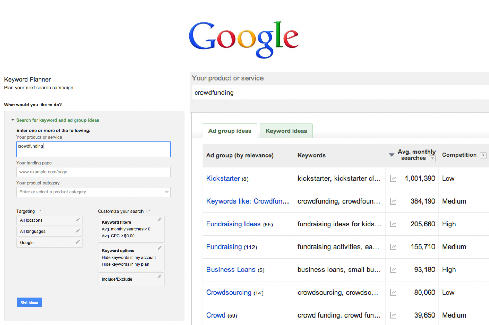

Then you want to further validate this market with some modern tools, including Google’s Keyword Planner and Facebook’s Advertiser Tools. (Figures 7-8).

If that proves fruitful, you should develop a simple landing page by using a service like Launchrock, photos from iStockphoto, and icons from iconfinder. You may also want to read up on some basic SEO. We’ll mostly focus on the crowdfunder, but Launchrock can be a complement to that approach. If your users need to see flows to understand the product, you will want to create some wireframes (see Figure 10).

Finally, you want to allocate a small Google Adwords or Facebook Ads budget to test out the market, and see how many conversions you get.

The overall concept here is to establish that a market exists before building a so-called minimum viable product (MVP). This process is related to some of the ideas from the Lean Startup school of thinking. Now, the ideas from this school can be taken too far. . . as Henry Ford famously noted, if he had asked his customers what they wanted, they would have asked for a faster horse. But most people new to startups aren’t in danger of talking to too many customers.

facebook.com/advertising

FB Ads: Outstanding census tool for doing realtime census of people interested in a specific idea.

Fantastic for bottoms-up market research.

Figure 7: Facebook’s realtime census tool is one of their most underappreciated features. Go to facebook.com/advertising and log in. Then begin creating an ad, and you’ll see the realtime census tool depicted above. You can use this to complement the Google tools and do some incredible realtime market research. For example, you can find the number of men ages 18-34 in Oregon who have an interest in snowboarding. These kinds of numbers let you get quick upper bounds on market sizes.

adwords.google.com/ko/KeywordPlanner

Google Adwords' Keyword Planner gives you bottoms-up statistics on search queries. This is more suitable for assessing purchase intent

than determining the number of individuals with a given interest.

Figure 8: You can use Google’s Keyword Planner at adwords.google.com/ko/KeywordPlanner to help estimate market size. Simply figure out some keywords related to your market, plug them in to get daily search volumes, and estimate what fraction of those would actually convert and at what price point. Use a few different values to get rough lower and upper bounds for the market. Then repeat with a few other related keyword sets to triangulate on a result.

A framework for determining product tiers

Once you’ve got your overall market that you’re targeting, you’ll need to come up with a product idea. For now let’s call that your moment of insight and creativity. If you have that product idea, though, in what order do you build features? First, read about Kickstarter product tiers and trends. The heuristic price points in this post are a good start, but we can supplement this with a little bit of theory, as shown in Figure 9.

The basic idea is that the ultimate market research is a table with 7 billion rows (one for each person), N columns on their attributes (e.g. location, profession) and K columns (one for each product version), with each entry giving the amount that person will pay for those features. Now, of course you won’t be able to sample all 7 billion, but you can sample a few hundred (e.g. with Google Consumer Research Surveys or Launchrock landing pages), and this gives you a conceptual framework for how to set up your product tiers.

Continuing with the conceptual example, in Figure 9 the CEO with PersonID 3 (i.e. the 3rd person out of 7 billion people) wants your product so much that s/he will pay up to $1000 for the version 1 with features 1 and 2. The vast majority of people will pay $0 no matter how many features you add. Histograms on these columns give the range of pricing that the market will tolerate, and allow you to estimate the amount of revenue you will make on each version (see in particular Spolsky on price segmentation). In particular, you want to confirm that you will make enough money on version 1 to pay for version 2. If this is not the case, you should rearrange the order of features until it is true, at least on paper.

If you are seriously considering starting a business, paying $250 for a demographically targeted survey with 500 responses will save you much more than that in the long run in terms of time/energy expenditure, at least if you’re in the US. Even spending $1000 to seriously evaluate four ideas will be well worth it in terms of the time/energy savings (though you should do one survey and review the results before you commit to doing more). If you genuinely can’t afford this, ask 10-20 of your friends how much they’d pay for different version of your product, or run a poll on Facebook. You will find that early feedback on pricing and features - even biased feedback - is greatly superior to none at all.

Figure 9: A conceptual framework for selecting product tiers and prioritizing features/versions.

Once you've settled on a market and a broad product idea, you need to think about exactly what your product versions will be and what features you will prioritize in each version. Here's a simple conceptual framework to guide that process, ensuring that you make enough revenue from each step to fund the development of the next stage.

Step 4: From your survey, what does the histogram of maximum prices ("reserve prices") look like for v1, and what's the estimated revenue?

6.9e9 (most will never buy )

~

PersonID 3 adds to the count of 100,000 people worldwide

who'd buy v1 at a max price of $1000

Step 5: Calculate market size

Rough global market size for v1 with perfect segmentation (100,000) * $1000 +

(10,000 * ($1100 + $1200)) + (1000 * ($1300 + … + $2000)

= $136.2M

Rough global market size for v1 priced at $1000: $128M

Is this greater than the cost of v1's features? In this case, yes.

16

Step 1: What is the maximum price each demographic would pay for each version of your product? You can't assess all 7e9, but you can survey a subset.

PersonID | Job | Employer | Age | Gender | Version 1 | Version 2 | Version 3 |

1 | Engineer | Exxon | 32 | M | $100 | $200 | $200 |

2 | Mechanic | Self | 23 | F | $0 | $10 | $10 |

3 | CEO | Startup Co | 39 | M | $1000 | $1500 | $2000 |

4 | Barista | Starbucks | 22 | M | $0 | $0 | $0 |

... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

7e9 | Scientist | NIH | 27 | F | $0 | $0 | $0 |

Step 2: What features are associated with each version? | |||||||

Feature 1 | Feature 2 | Feature 3 | Feature 4 | |

Version 1 | Y | Y | N | N |

Version 2 | Y | Y | Y | N |

Version 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y |

... | ... | ... | ... | .. |

Step 3: What is the estimated cost/time to build each feature?

Cost | Time | |

Feature 1 | $1,000,000 | 50 days |

Feature 2 | $50,000 | 100 days |

Feature 3 | $500,000 | 200 days |

... | ... | ... |

# of people who would buy at this price

100,000

10,000

1000

100

$0 $1000 $2000

Version 1: Reserve Price

Once you feel that you have a market, you’ll want to design a mockup of your product’s website, also known as a wireframe. For the purposes of this class, we’ll presume two things: first, that every product in the class will have a web component. Second, that the product itself will be initially marketed through your own crowdfunding website, but will ultimately have its own dedicated website. Indeed, this crowdfunding website can ultimately morph into the product website over time.

Wireframing

There are many excellent wireframing tools, and we’ve picked out four in particular that are of interest Figure 10. For editing on the computer, Omnigraffle Pro is very good for offline editing, Lucidchart is useful for collaborative wireframing, and Jetstrap makes it easy to convert a final design to Twitter Bootstrap. For converting offline pen and paper mockups, POP (popapp.in) is really worth trying out. Try these tools out and find one you like; your main goal is to produce sitemaps and detailed user flows that look something like this.

omnigroup.com/products/omnigraffle Advantage: Offline support, many stencils at Graffletopia, and excellent keyboard shortcuts |

lucidchart.com Advantage: Supports multiplayer collaboration and works with Google Drive |

|

|

jetstrap.com | popapp.in |

Advantage: Directly export to | Advantage: Prototype |

HTML/CSS/JS and mockup | with pen and paper and |

with Bootstrap objects | easily make clickable workflows |

Figure 10: A survey of four useful wireframing tools. Pick the one that works best with your style.

Copywriting

Here are some high level copywriting principles.

Homepage message: If it’s not a homepage message, it’s not a message. Don’t expect visitors to figure out what the product is about on the third page in; your enemy is the back button. That said, only spend energy on the homepage if it’s a significant source of customers. If it isn’t (e.g. if your sales come through a salesforce), you can leave the homepage alone for a surprisingly long time.

Work backwards from the press release: Amazon writes the press release before they build the product. In doing this, you will find yourself figuring out what features are news and which ones are noise. Take a look at their press releases to get a sense for tone.

Someone is wrong on the internet : Get a friend, have them pull up as many competitor webpages as possible, and you will quickly find yourself explaining to them why those companies are terrible and why yours is different. This is valuable. Write down your immediate gut reaction as to why your product is indeed different. Put this into a feature matrix (example) and then determine whether your new features really differentiate your product substantially.

Simple and factual : Do your best to turn vague features (“PageRank provides better search quality”) into concrete facts and statistics (“X% of searchers who used both Blekko and Google preferred Blekko. Find out why.”). Use Oracle style marketing: less is more, hammering one point above the fold and keeping the rest in the secondary copy.

Call to action: You want someone to do something when they come to your page, like buy something or sign up on an email form. Make sure you reiterate this “call to action” many times. Make the call to action button cartoonishly large and in a different font.

You can put these principles to work with your crowdfunder.

Design

Your first goal with the wireframe should be functionality and semantic meaning: what does the product do? Your second goal is the marketing copy: how do we explain what the product does in words? Your final goal is the design: how do we make the site and product look beautiful and function beautifully? Let’s go through some high-level design principles.

Vector and Raster Graphics: The first thing to understand about design is the distinction between vector and raster graphics. Whenever possible, you want to work with vector objects as they will scale well and are amenable to later manipulation. Raster images are unavoidable if you truly need photos on your site, but you should strive to minimize them for your MVP.

Alignment, Repetion, Contrast, Proximity : The Non-Designer’s Design Book by Robin Williams is reasonable as a next step, with the four principles summarized here. You can see what these four principles look like in practice: Alignment, Repetition, Contrast, Proximity. A good strategy is to look at the examples, try to internalize the lessons, create your design without thinking too much about them, and then re-apply them over the design at the end.

Fonts and Icons: In terms of getting something reasonably nice together quickly, you should make heavy use of fonts. Because fonts are vector graphics specified by mathe- matical equations, they are infinitely manipulable with CSS transforms built into every browser (which we will cover next week). The FontAwesome library also gives scalable vector icons, which are often useful for quick mockups when enlarged in size. Even if not the perfect image, the fact that these complex images can be generated in a single keystroke and rotated/colored with a few more make them quite good for quick proofs- of-concept. With a bit of practice, one can get to a reasonably good looking prototype with pure fonts and Unicode characters.

Stock Photos, Videos, Animations: Use iStockphoto as a visual companion to the Key- word Tool External. Often the key to a good presentation or webpage is to put an abstract concept into visual form. Stock photographers have actually thought about these issues; here’s an example for launching a business. One point: don’t use stock photos in which people are looking at the camera. That’s what makes a stock photo look cheap. A good signal of a lower quality site is that it has inconsistent padding, doesn’t use https properly for checkout, and/or uses stock photos of this kind. Again, this is bad, while this is passable. You might also consider reshooting a stock photo with your product so that it looks custom.

Use Bootstrap, Themeforest, 99Designs, Dribbble: When it comes to turning your wire- frames into HTML/CSS/JS, don’t reinvent the wheel. Design is information and is becoming commoditized. Bootstrap is a free CSS framework we’ll be using through the course. Jetstrap, mentioned previously, is a wireframing tool that exports to functional HTML/CSS with Bootstrap. Themeforest is a set of slightly more expensive ($9-12) templates. 99Designs is a few hundred to a few thousand bucks for a logo or web- page revision. And Dribbble is an excellent resource for finding a contract or full time designer.